A few questions here.....

1. Have a higher chance of success (not quite the same as wasting time)

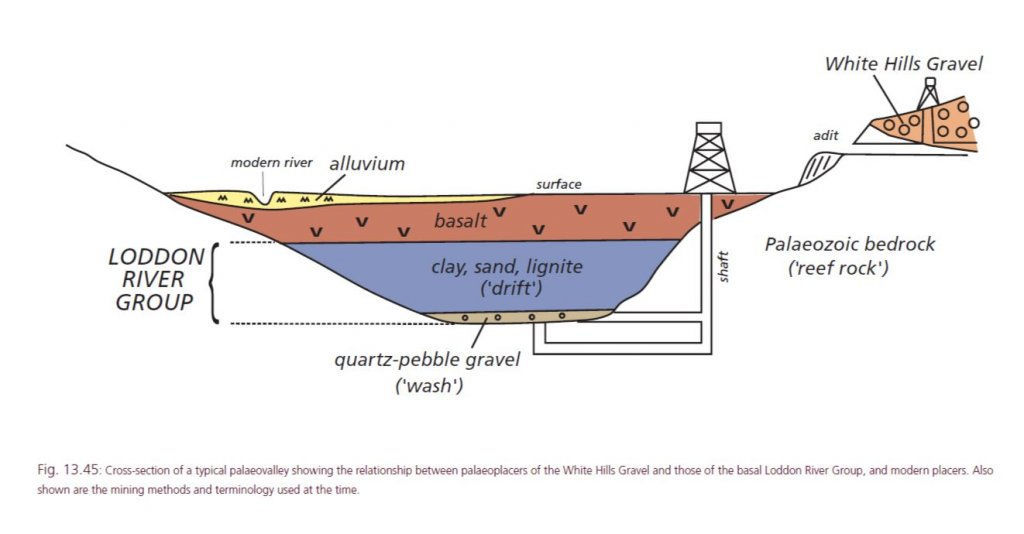

2. Most may have been palaeoplacer in the past, but for the reasons you state most that is AVAILABLE to you now is in modern rivers or near exposed and uplifted older river gravels. Not only is digging a shaft hard work, but in wet ground it was extremely dangerous with up to a death per day on some goldfields. Also, almost the entire Victorian forestry industry up to 1900s was devoted to timber for mines and to a lesser extents ports - they did not know how to season hardwood so it was not a choice for housing. Try chopping down that many trees now to provide the close timbering required in underground alluvial mines and see how you go (you'll be drawn and quartered)- there are alternatives to timber but not cheap because you are basically trying to keep wet sand and mud from burying you. And you will have to pump in most cases.....

3. Detecting is definitely the more fun way to go as a hobby and you can get gold shed from uplifted alluvials or from reefs being eroded away at surface (in the adjacent soil) as well

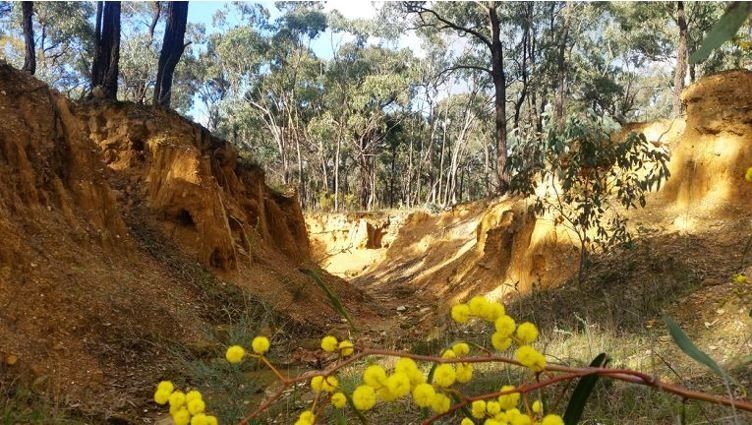

4. You can fairly easily prospect uplifted gravels shown on geological maps - not a lot to learn. The gravels containing the gold will usually be identified as Tertiary (particularly Older Tertiary) or Palaeogene. And they will usually be called fluvial or river gravels (many other gravel types lack gold). You need to prospect in the soil near what would have been the base of the gravels when they formed (where they lie on older bedrock). Not just everywhere where they lie on bedrock, but preferably the lowest former base, that would have been the active stream channel. Obviously old workings in the gravels that are shown on the maps are a clue to where to look. Needs a bit oif learning but not a lot. Uplifted gravels also have the advantage that the old-timers often lacked water (they would sometime stockpile for up to 3 years waiting for rain), so they could be very inefficient in getting all the gold in such cases. Mones weres till working such gravels in the 1980s (eg near Avoca in Victoria)

Hope that helps.

..."4. You can fairly easily prospect uplifted gravels shown on geological maps - not a lot to learn. The gravels containing the gold will usually be identified as Tertiary (particularly Older Tertiary) or Palaeogene. And they will usually be called fluvial or river gravels (many other gravel types lack gold). You need to prospect in the soil near what would have been the base of the gravels when they formed (where they lie on older bedrock). Not just everywhere where they lie on bedrock, but preferably the lowest former base, that would have been the active stream channel."...

..."You need to prospect in the soil near what would have been the base of the gravels when they formed (where they lie on older bedrock). Not just everywhere where they lie on bedrock, but preferably the lowest former base, that would have been the active stream channel."...

goldierocks how does one work this out? Is it possible from a geological map? Can you find the base of the gravels off modern topography?